A Different Top 10 List of Grant Writing Mistakes (Part 1)

I know what you’re thinking: not another top 10 list of grant writing mistakes!

Bear with me. This list is a little different. Most top 10 lists of grant writing mistakes include things like:

Too much jargon

Long-winded answers

Ignoring funder’s priorities and guidelines

I approach things a little differently. My unique experience comes from having a Master of Public Health degree and experience as:

a grant-funded program director,

an independent federal grant evaluator,

a community-based grantmaker, and

a nonprofit consultant.

This is the first part in a 3-part blog series. Given the current political climate surrounding public health, part 1 contains insight from my public health education and experience.

Part 2 will focus on my evaluation experience, and part 3 will share the wisdom I gained from overseeing a community-based grant funding program.

“Mistakes are the portals of discovery.”

Key Takeaways:

WHAT: Increase your chances of funding by using evidence-based or evidence-informed practices. Investing in something that has been shown to affect positive change is not only cost-effective, it can be life-saving.

WHO: Funders often want to ensure their funding goes to the populations and communities that need it most. Understanding the social determinants of health, health equity, and health disparities allows us to further evaluate evidence to determine our target audiences.

HOW: One of the pillars of evidence-informed practice is to incorporate the voices of the populations you serve in the into the design and evaluation of your program. More funders are now asking applicants their methods for ensuring meaningful community participation.

#1: Lack of Evidence-Based or Evidence-Informed Practices in the Program’s Design

You might have started or joined up with a nonprofit because of your passion for helping others. But even the best of intentions can result in unintended harm and needless morbidity and mortality. When we design programs based solely on “common sense” or on our own experience and ideas, not only could we waste money on an ineffective intervention, but people could suffer significant harms, sometimes resulting in death.

What is evidence-based public health?

Consulting the latest, most reliable research available

Incorporating expert opinions

Involving the community you’re targeting in the program design and evaluation process

Here are two short video overviews:

So, how do you find, interpret, and apply public health evidence?

Here are some of my favorite resources:

This video will help you evaluate the levels of evidence you’ll come across in scientific literature.

#2: Ignoring, Neglecting, or Minimizing Health Disparities

“Health disparities are preventable differences that populations experience in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities. When people have limited access to resources they need to be healthy, they are more likely to experience health issues” (CDC).

Addressing health equity and reducing health disparities are central to our approach in identifying and serving those most in need. By examining the social determinants of health—such as income, housing, education, transportation, and access to healthcare—we are able to better understand the root causes of poor health outcomes in marginalized communities. This evidence-based framework allows us to prioritize populations that have been historically underserved or disproportionately affected by systemic barriers. By integrating these insights into our program design, we ensure that funding is directed toward interventions that promote equitable health outcomes and close the gap in access, resources, and opportunities for well-being.

Social Vulnerability Index

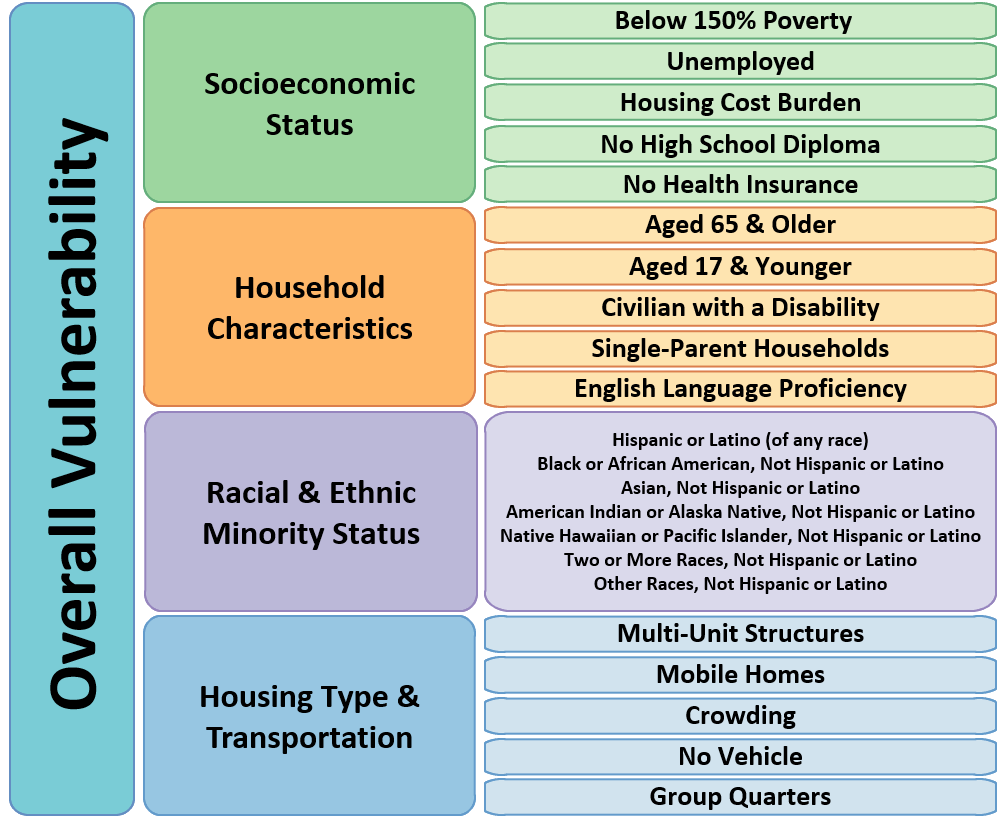

The current CDC/ATSDR Social Vulnerability Index uses 16 U.S. Census variables from the 5-year American Community Survey (ACS) to identify communities that may need support before, during, or after disasters. These variables are grouped into four themes that cover four major areas of social vulnerability and then combined into a single measure of overall social vulnerability.

Resources:

Disparities and Health Equity: Some Key Facts for National Minority Health Month

America’s Health Rankings (explore data by topic area and state)

Community Resilience Estimates (data on resilience by state and county)

Social Vulnerability Index (may be taken offline during Trump era)

Kaiser Family Foundation (also see their Racial Equity & Health Data Dashboard)

Health Equity Tracker (interactive tool)

#3: “Nothing About Us Without Us:” Engaging the Population You Serve

“The World Health Organization (WHO) defines community engagement as: “a process of developing relationships that enable stakeholders to work together to address health-related issues and promote well-being to achieve positive health impact and outcomes.” This effort represents a collaboration between public health professionals, government officials and community members to implement public health initiatives.

That said, it’s important to note that “community” is not just limited to a civic definition. It may reflect faith-based organizations, cultural/racial groups or even life-stage groups.” (Source)

When Community Is Left Out of Discussion: Squandering Time, Money, Resources, and Goodwill

When public health leaders fail to meaningfully engage communities, the consequences can be severe. In the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, stigma and a narrow understanding of who was affected delayed an effective response. Only when the disease began impacting a broader population did society recognize the need for inclusive, community-wide action.

Similarly, during Hurricane Katrina, a lack of local infrastructure and community organization led to devastating delays in aid and exposed the consequences of overlooking the role of local engagement in emergency preparedness and response.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health efforts initially struggled in many communities of color due to a lack of culturally appropriate messaging, historical mistrust, and minimal input from local leaders. Vaccination campaigns, for example, saw limited success until public health agencies began partnering with trusted community organizations, faith-based groups, and local influencers. Effective public health responses require the voices, trust, and leadership of the communities most impacted.

What Can Happen When the Communities We Serve Don’t Have a Seat at the Table and We Don’t Center Our Work Around Equity: The Tuskeegee Study

The Ethics of Community Engagement

Everyone has the right to be involved in healthcare decisions that affect them. Public participation in health planning, research, and policy-making is both a moral obligation and a way to empower communities. By engaging diverse voices—especially those often left out—health officials promote respect, equity, and shared decision-making. This inclusive approach leads to more effective programs, fairer resource distribution, and better outcomes by addressing the root causes of health disparities. (Source)

More Than Lip Service or Tokenism: True Community Engagement

True community engagement is NOT:

Resources and meetings to inform the community/local community-based organizations (CBOs) of programs and initiatives otherwise designed via a top-down approach

Occasional meetings or research efforts (e.g., surveys, community needs assessments) to secure the input of the community or CBOs on new programs or research studies

Community consultations that only seek advice but do not recognize the decision-making role of local communities

“Expecting reciprocity” for efforts that benefit local communities

Capacity building efforts that aim to “teach” our own ways of doing things instead of addressing community needs and increasing community influence

Any kind of community/CBO involvement in which final decisions are still with health departments, government agencies, academia, and other kinds of organizations outside of the community

Strategies to Strengthen a Culture of Engagement

Make community concerns, input and feedback a public health priority.

Identify and revise organizational processes where community members who live with inequities can make sustained contributions as experts.

Require information-sharing between public health and community members and ensure staff and community share training on health equity.

Support community-based organizations to build engagement strategies and principles into what they do.

Formally and publicly recognize community member contributions to public health work.

The 5 stages of Community Engagement for Public Health (view full PDF)

Resources:

Summary

This first installment of a three-part blog series offers a fresh perspective on common grant writing mistakes, particularly through the lens of public health. Unlike typical top 10 lists, I use my experience as a public health expert with experience as a grant evaluator, grantmaker, and nonprofit consultant to focus on critical, often overlooked issues in program design.

These include the failure to use evidence-based practices, the neglect of health disparities and social determinants of health, and the lack of authentic community engagement.

Let’s work together to end health disparities for everyone.